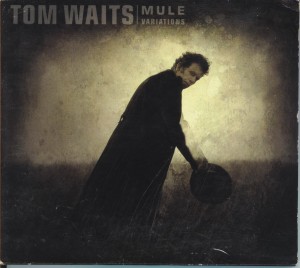

“There’s no better songwriter when it comes to weepy ballads of serious content,” Rita says as we drive into West Hollywood. “My two favorites are on the Mule Variations album: ‘Georgia Lee,’ about a 12 year-old girl found dead in a small grove of trees, and ‘Take It With Me,’ which is Tom singing about the love he has for his wife and how he loves her heart so much he’s going to take it with him when he goes. Then there’s ‘A Little Rain’ from Bone Machine—another young girl who climbed into a van with a vagabond and the last thing she said was ‘I love you, mom.’ Heartbreakers! And listen to ‘Bend Down the Branches,’ ‘You Can Never Hold Back Spring,’ and ‘Fannin Street,’ from Orphans; and his takes of ‘Lucky Day’, and ‘I’ll Shoot the Moon,’ on Glitter and Doom. Rougher, darker and more soul searching than when he first did them.”

“There’s no better songwriter when it comes to weepy ballads of serious content,” Rita says as we drive into West Hollywood. “My two favorites are on the Mule Variations album: ‘Georgia Lee,’ about a 12 year-old girl found dead in a small grove of trees, and ‘Take It With Me,’ which is Tom singing about the love he has for his wife and how he loves her heart so much he’s going to take it with him when he goes. Then there’s ‘A Little Rain’ from Bone Machine—another young girl who climbed into a van with a vagabond and the last thing she said was ‘I love you, mom.’ Heartbreakers! And listen to ‘Bend Down the Branches,’ ‘You Can Never Hold Back Spring,’ and ‘Fannin Street,’ from Orphans; and his takes of ‘Lucky Day’, and ‘I’ll Shoot the Moon,’ on Glitter and Doom. Rougher, darker and more soul searching than when he first did them.”

“He calls those his Weepers or his Bawlers,” I say. “Orphans has one disc of just the ballads, another of the shouts, which he calls Brawlers or Creepers, and a third he calls Bastards, which is a place for the strange and eclectic. 56 songs, three years in the making, and covering the full array of Tom Waits characters from carnival barker, preacher, and country singer to soul balladeer, cabaret singer, and storyteller.”

“Well, give me his Bawlers,” Rita says. “They get to me like no other singer.”

“I’ll take the Brawlers,” Simon pipes in. “I like my Waits coarse, rough, like sandpaper. When he screams the ‘Earth Died Screaming,’ you better believe that’s the way the world will end. Screaming.”

I recall what Elizabeth Gilbert wrote about this side of Waits, where he has shown “a lifelong desire to unbuckle those pretty melodies, cleave them into parts like a butcher, rearrange the parts like into some grotesque new beast and then leave it in the sun to rot. It’s almost as if he’s afraid that if he stuck to writing lovely ballads, he might become Billy Joel.”

“Well, where do you place the narratives,” Smay asks, “when Waits just talks through a story, like ‘Shore Leave,’ from Swordfishtrombones, ‘9th and Hennepin,’ from Rain Dogs, ‘Circus,’ from Real Gone, ‘What’s He Building?’ from Mule Variations, or ‘Tom’s Tales’ from the Glitter and Doom album? These are all distinctive Waits originals, what you come to expect from him: the story-telling bard putting a drum or piano behind his spoken-word pieces. And the stories he tells are usually haunting, creepy, mysterious and unresolved. Just the way he sees life.”

“I’m not a big fan of the spoken pieces,” Rita says, “because you don’t really listen to them over and over again, like you do with his ballads. Even the screeching brawlers, how many times can you hear them before you say, OK, enough, let’s move on. But his weepers, those will last forever. Look at his first album, Closing Time, it’s been 35 years since he put that out and it still holds up. They’re songs for the ages. ‘Martha.’ ‘Rosie.’ ‘Virginia Avenue.’ ‘Goin’ Down Slowly.’ ‘Grapefruit Moon.’’ Lonely.’ ‘Closing Time.’”

“Don’t forget ‘Ol’ ‘55,’ Simon adds. “And ‘Jersey Girl’ from Heartattack and Vine. Springsteen covered that one. ‘Nothin’ else matters in this whole wide world,/when you’re in love with a Jersey girl,’” he sings, off-key, but to the point.

“I saw Springsteen do ‘Jersey Girl’ at Giants Stadium. The crowd went nuts, singing along, swaying their arms. It’s one of his best songs,” Rita says.

“Yeah, but listen to Tom sing it,” Simon says. “You can go to YouTube and just listen. The Boss is sweet, but Tom man, when he says he’s going to cross the river to the Jersey side, you feel his urgency, his hunger. Nobody covers Tom Waits like Tom Waits.”

A woman named Martha joins our conversation to add, “Nobody’s mentioned what may be his best, or signature song, ‘Tom Traubert’s Blues,’ from Small Change. Where he sticks in ‘Waltzing Matilda.’ God, that song gets me every time I hear it.”

It seems everybody on the bus wants to say something about Waits. And it’s all positive. Why else would they be on this tour?

“One other anecdote,” Rita says. “I saw him on a TV show sitting at a piano with a bottle of booze on the top of the piano. When questioned about it, he said, ‘I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.’ I never forgot that quote because it was such a musical play with words.”

“I like what one writer wrote about him,” Simon says, “’He can show you what you already know and make you believe it again.’”

Follow

Follow

Comments are closed.